Nuking North Carolina: The Goldsboro “Broken Arrow” Incident

Hear this story in audiobook format for only 99 cents.

Unbeknownst to most Americans, the world as we know it has almost ended several times over.

One of the better-known examples is that of “The Man Who Saved the World”—Lt. Col. Stanislav Petrov, a Soviet officer overseeing the missile attack early-warning launch system in Moscow.

“LAUNCH” was blaring in large red letters across the monitors. According to the computer system, the United States had launched a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union.

Another monitor buzzed. And another, and another, until the computers were warning Petrov that a total of five intercontinental nuclear warheads were barreling toward him.

Protocol dictated that Petrov should report the incoming missiles and initiate the response system. But he knew that doing so would trigger a chain of events launching hundreds of USSR warheads at the United States. He couldn’t take action until he was absolutely certain.

The screens flashed in front of him: LAUNCH. LAUNCH. His subordinates urged him to make a decision. It seemed kind of important, they said.

If Petrov set Moscow’s nuclear strike retaliation procedure into motion, and catapulted warheads to California, the United States’s own nuclear response system would initiate and even more nukes would enter the atmosphere.

It would be total annihilation for both countries—all within the span of minutes—all resting on Petrov’s shoulders.

“No pressure or anything,” a subordinate said, “but the computers seem really mad.”

Sweat beaded on Petrov’s forehead and pooled under his arms; his hands tingled and his vision swirled.

“Don’t report it,” he said, finally. “It could be an error.”

And it was. The warning system had been tricked by the sun’s reflection off the clouds. Which, if you ask me, is a pretty fucking huge flaw in the design of such a system.

For those of us who watched HBO’s Chernobyl, such an oversight doesn’t seem so surprising (and Petrov’s decision seems even more brave). Dumb commies, am I right? Well not so fast. The U.S. has a nuclear flub story of its own.

I’m speaking specifically about the time we kind-of-sort-of accidentally dropped a nuke on Goldsboro, North Carolina.

The “Broken Arrow” (a military term referring to any whoopsies on a nuclear scale) in North Carolina spawned as the result of an “insurance policy” designed to respond quickly if the Soviets had someone less level-headed than Petrov behind the launch button…

Around midnight on January 23rd, 1961, a lone B-52 Stratofortress bomber cruised along the American Atlantic coastline. It carried eight crewmen and two MK-39 thermonuclear warheads—each of them 250 times more powerful than the atomic bombs that devastated Hiroshima.

Despite nearing the tail-end of a 25-hour flight, its pilot, Major Walter Scott Tulloch kept a steady focus behind the yoke as he eased the ship into position behind an airborne fuel tanker.

This was their second refuel of the mission and one of hundreds he’d logged during his years as a bomber pilot. It was with little conscious effort that he held the plane perfectly steady for the tanker to guide a fuel line to its nose.

The airborne refueling process, 25-hour flight missions—none of these were a novelty to Tulloch or his crew—they’d been carrying out mirror copies of these missions for months now as part of the US nuclear response strategy: if ground forces were wiped out by a sudden nuclear attack from the Soviet Union, Major Tulloch and any other airborne bombers would launch an immediate nuclear airstrike against the motherland in retaliation—Petrov’s worst fears brought to fruition.

On this night their monotony would be broken.

A voice crackled over the cockpit radio—“Pilot, it looks like you’ve got a fuel leak coming from your right wing.”

Just after, one of the crew members reported fuel leaking into the bomb bay and soaking the wheel wells. Tulloch rattled a quick command, ordering the crew to shut off all non-essential breakers to prevent any potential sparks.

The fuel tanker detached its line from the B-25 and Tulloch banked the plane and turned the nose toward the coastline and Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in Goldsboro, North Carolina.

An eerie silence haunted the crew as their wounded ship droned over the North Carolinian countryside. In the bomb bay the two thermonuclear bombs hung in their mounts. At the front of each was a horizontal arming pin that, when removed, would activate their detonation sequence. The chain lanyards attached to the pins tinkled against the olive-green steel of the bomb casings.

Far below, Americans slept—blissfully unaware that unimaginable catastrophe was a hair’s breadth away.

About twelve miles from the base, Tulloch eased the plane below 10,000 feet and dropped the landing gears in preparation for a long, steady landing. But just as they settled into their descent path, a boom echoed through the aircraft and the yoke jerked left. Tulloch straightened it out just as another boom shuddered the plane and swung it hard right. He and the copilot both yanked as hard as they could, but it quickly became clear they had lost control of the ship. Tulloch gave the order to bail out.

He and his co-pilot Richard Rardin jumped from the aircraft in quick succession, deploying their parachutes a few hundred feet from each other. Tulloch pulled on his guide lines to spin himself around. He scanned the midnight air and saw four other parachutes including Rardin’s. He prayed the other three crew members had made it out. And then, in the blanket of sudden silence, he watched helplessly as the doomed B-25 disappeared into the darkness.

The B-25 slid into a haphazard spin. Centrifugal force pressed the three remaining crewmen against the cold fuselage as they fought for their exits. The plane creaked and moaned and the air screamed against the roar of the engines. The bombs rattled.

The airplane began to break apart over a tobacco field in Faro, North Carolina. Rivets popped and the aluminum skin on the wings and fuselage tore like tin foil. One of the bombs broke free from the bay and deployed its parachute, drifting down to land harmlessly in a tree with its arming pin safely intact.

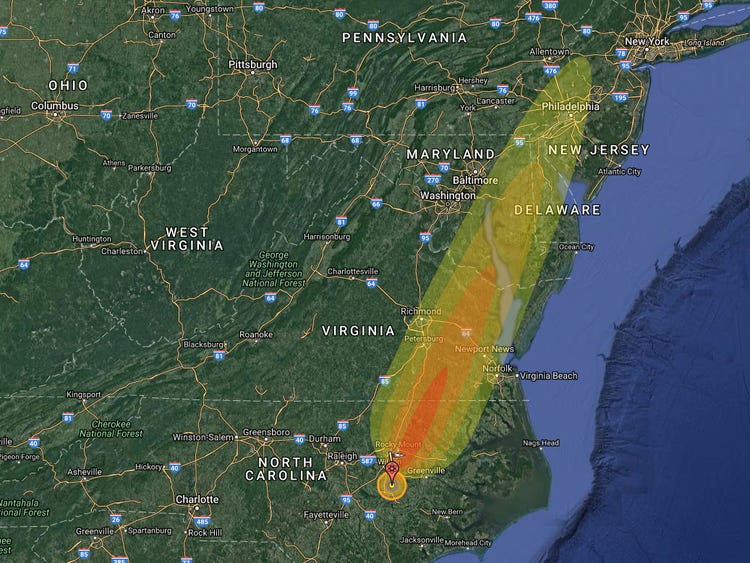

Part of the second bomb’s mount snapped loose and the lanyard caught on a jagged spear of torn aluminum. The safety pin pulled free, arming the Bisch generator which provided the bomb’s internal power. It then broke completely free from the bomb bay and in the process extracted the deployment cable which whirred the generator to life. The warhead slipped out of the blossoming midair wreckage and began its detonation sequence. The baroswitch arming system began calculating the optimal detonation altitude to inflict maximum damage—a 100% kill zone of seventeen miles would surround the initial blast, and lethal nuclear fallout would seep through Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York.

The precision mechanisms inside the warhead were ticking along as intended: The Bisch generator, the baroswitch arming system, high and low voltage thermal battery activation—everything except the parachute deployment. Because its chute failed to deploy, the bomb screamed into the tobacco field at 700 miles per hour and barreled into the mud, scattering debris in all directions and rocketing its plutonium core into the night air. The secondary core, comprised of weapons-grade uranium, burrowed some 200 feet into the earth.

Hours later, a recovery team led by munitions expert Lieutenant Dr. Jack ReVelle entered the crash sites and began a cleanup process that would remain shrouded in mystery for over fifty years.

The first bomb was found resting against a tree with its parachute entangled in branches. The team used a crane to ease it carefully onto a flatbed and haul it away.

At the impact site of the second bomb, they were presented with a quagmire of debris. They began to sift through the jetsam, collecting everything they could. ReVelle and his men spent two days in the tobacco field, with little food, in the freezing sleet and snow, working on shifts to dig through the wreckage.

The tail piece of the bomb was discovered twenty feet underground. The plutonium core was found in a neighboring field. And then they found the most disturbing piece of evidence— the bomb’s arm/safe switch. Years later ReVelle recalled the moment when it was found:

“Until my death I will never forget hearing my sergeant say, ‘Lieutenant, we found the arm/safe switch.’ And I said, ‘Great.’ He said, ‘Not great. It’s on arm.’”

The bomb should have exploded. The muddy rows of tilled earth they stood upon should have been a crater spanning a third of a mile wide, surrounded by a ring of extermination killing every human, plant, and animal within seventeen miles.

What had prevented the worst from happening?

As they pulled the switch mechanism out of the mud and hauled it to the surface on a wooden ladder, none of them knew the answer. They couldn’t afford to focus on anything but the immediate task at hand. With the switch set to “arm,” the bomb could still explode at any time.

They continued the nerve-shattering excavation process for eight days, shipping each component—both radioactive and explosive—to Seymour Johnson Air Force Base.

After he returned to base, Jack sat down to write a letter to his parents. As he lifted the pen, his hand began trembling. “I thought to myself, ‘My God, where have I been? What have I been doing?’ ”

Later it would be discovered that the only thing preventing detonation had been a single cockpit-controlled low-voltage safety switch. Three out of four safety mechanisms had been set to arm.

Several parts of the bomb were never found. To this day, somewhere deep in the soil below North Carolina, a uranium core rests.

For decades rumors persisted of a nuclear bomber wreckage over Goldsboro. It wasn’t until 2013 that the report was declassified and Jack ReVelle could tell his story.

Because the “Broken Arrow over North Carolina” happened at the height of the Cold War, it’s likely that a nuclear explosion would have erupted into full-scale nuclear war. But even had cooler heads prevailed and that crisis been averted, the devastation of the single explosion would have changed American life as we know it.

“You would’ve created a bay of North Carolina, completely changing the configuration of the East Coast of the United States,” Jack said. “And the radiation could have been felt as far north as New York City.”

SOURCES

NPR. “8 Days, 2 H-Bombs, And 1 Team That Stopped A Catastrophe“

Business Insider. “A thermonuclear bomb slammed into a North Carolina farm in 1961 — and part of it is still missing”

Sedgwick, Jessica. Bombs Over North Carolina

Hardy, Scott. “The Broken Arrow of Camelot: An Analysis of the 1961 B-52 Crash and Loss of the Nuclear Weapon in Faro, North Carolina”. East Carolina University.

A CLOSE CALL- Hero of ‘The Goldsboro Broken Arrow’ speaks at ECU

Want more of history's lost gems?

Sign up for my email list to be notified when new stories, books, or audio files are released!

© Copyright 2020 Tom Edwards